This is a Part 3 of a series of articles on: Why Interest Rates Would Stay Low No Matter What the Fed Says or Does. Read Part 1 and Part 2, please.

The brewing dramatic slowdown in China should lead to a severe recession and almost inevitable crisis – we can only debate its scope and length. But this is how the US interest rates could be affected and how the Fed could react. Let’s relive the last Asian crisis of 1997 for some analogies.

During 1986 – 1996 the economy of Thailand grew north of 9% per year, the highest pace worldwide at the time. As the Thai central bank mismanaged the Thai baht, which was pegged to the basket of currencies, Thailand’s economy came to an abrupt halt. There was massive layoffs in the Real Estate, Finance and Construction industries and many laborers had to return back to their villages and more than half of a million foreign visiting workers were dispatched home. The Thai stock market collapsed by 74%. Finance One, the largest Thai private financial institution in 1996, went belly up and was sarcastically ridiculed as “Finance to Zero”.

The story of South Korea in 1997 had similar twists of unbalanced expansion. The banking industry was burdened with non-performing loans as major Korean companies were financing aggressive growth. Some high profile businesses failed to return to profitability and, ultimately, accumulated debt caused high profile restructurings. Kia Motors needed emergency loans and Samsung Motors’ venture was scrapped, and Daewoo Motors was sold to GM. KOSPI index was down 60-70%.

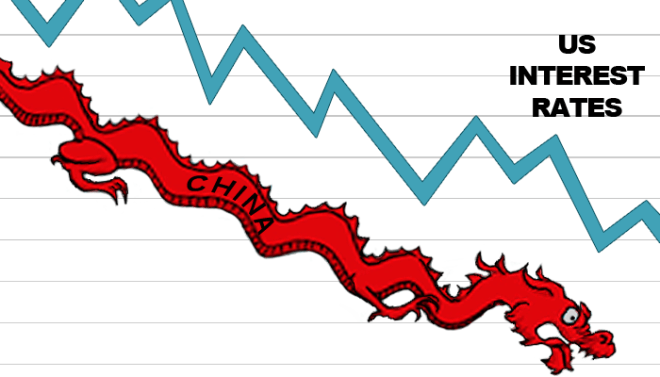

As crisis unfolded in Thailand and in Korea, US Interest rates (10YR) went down from 7.0% to 4.1% (predictable flight to quality and safety), despite the Fed’s inactivity (See the Figure 6). Eventually, the crisis dented many Emerging Markets including Russia, Brazil and Argentina. Then, the Fed started to react to the broadening crisis (and LTCM was one of indirect casualties that catalyzed that), effectively lagging equity indices there. Check how systematically Fed FFR moves lag market-driven changes to the 10YR yield, all driven by the agitated market.

Developments leading to the 1997 Crisis in Thailand and Korea (and across South-East Asia back then) have many similarities to modern China, if not in every detail but definitely in the spirit of 3 OVER’s (Over-built, Over-growth, Over-leverage). Long breakneck expansions never come without a steep price to bear. But there are 2 key disturbing difference between the Asian crisis of 1997 and the coming crisis in China:

1.Back in 1997 the size of the economy of Thailand was ~2% of the US GDP, but now the size of the Chinese economy is >65% of the US economy

2.Back in 1997 the Fed had ability to cut rates and now it doesn’t

So, if in 1997 a crisis of a handful of relatively small economies in Asia caused a meaningful bid to US treasuries and led to series of rate cuts by the FED, then what should we expect when the economy of China slides into a recession? I really wish the FED had room to cut rates preventatively… preferably, now.